Topic

This 2010 movie is set during the Black Death period in England as a monk and some soldiers set out to try and find out if a nearby village is truly escaping outbreaks of the plague or not. I talk about the plague itself in detail, describe all three major worldwide pandemics and then discuss the Black Death (which was from 1348-1353) in detail.

Sources

Estimate of world population: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estimates_of_historical_world_population

Origin of words

The most comprehensive source on The Black Death: https://www.amazon.ca/Complete-History-Black-Death/dp/1783275162

Review of said book: https://networks.h-net.org/node/19397/reviews/9667911/arnold-benedictow-complete-history-black-death

History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7513766/

Yersinia pestis: the Natural History of Plague: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7920731/pdf/CMR.00044-19.pdf

Dancing plague: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dancing_plague_of_1518

Sweating sickness: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweating_sickness

Plague of Athens: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plague_of_Athens

The Great Dying: https://historicipswich.org/2021/04/21/the-great-dying/

Mystery Illnesses: https://gizmodo.com/6-mysterious-disease-outbreaks-that-were-never-solved-1846609130

Plague is plague: https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(14)61331-8/fulltext

Theories on the cause of the Black Death: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theories_of_the_Black_Death

Plague from soil and a weeks-old dead mountain lion: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/14/6/08-0029_article

Identifying the cause: https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-bright-side-of-the-black-death

From 2001, an article disputing Yersinia as the cause: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg17223184-000-did-bubonic-plague-really-cause-the-black-death/

Justinian Plague: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1903797116

History in Charts, Justinian Plague: https://historyincharts.com/the-death-toll-during-the-plague-of-justinian/

Plague and Climate: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3174245/pdf/ppat.1002160.pdf

Biological warfare at the Seige of Caffa: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/8/9/01-0536_article

The Black Death origins: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/black-death-greatest-catastrophe-ever

Black Death timeline: https://www.britannica.com/summary/Black-Death-Timeline

Persecution of the Jews: https://academic.oup.com/past/article-abstract/196/1/3/1488091

Role of CCR5 mutations in plague resistance: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature02822

Medicinal plants of the lamiaceae family:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5964621/

Transcript

Hi folks, this is Tierah Ruins Things with Science, a podcast about the science of immunology & infectious diseases in pop culture. I am Tierah, and I am here to ruin your favourite tv shows and movies by telling you how badly they butchered science.

Today I’m going to be talking about the 2010 movie Black Death, starring Sean Bean, Eddie Redmayne, and Carice van Houten, among others. It’s available to rent on Apple TV and Amazon Prime if you’re so inclined.

Before doing this episode, I hadn’t actually seen Black Death, which is different from most of the episodes I’ve done already.

There aren’t too many movies featuring the plague, and I’d already seen Season of the Witch, but that didn’t really have much to do with the disease of plague and it wasn’t that great, so I didn’t want to cover that one.

I wanted to do something on plague because it was one of the most interesting diseases I studied in my undergrad, which was in immunology.

I think in social studies classes in high school I always found it morbidly interesting thinking about the plague and what it would’ve been like to live before antibiotics.

Even though I’ve studied this before, I did learn a lot about it as I researched, including the one thing that really makes the plague unique in its spread and probably explains why it was so successful and nearly wiped out all of Europe.

Before I start, I want to put this out there for those of you who don’t listen to credits at the end, if you have any movie or episode of a tv show that features an infectious disease that you want me to ruin with science, email me at tierahruinsthings@gmail.com or get in touch on social media and I’ll look into it and maybe do an episode on it!

Just please, not CSI. It’s too easy and there’s just too much.

[MUSIC]

The movie begins with an opening monologue that talks about the terrifying scale of just how far this disease reached and how many people it killed.

The most current, extensively researched source puts the estimated death toll between 60-65% of the European population, so saying that it would leave half the kingdom dead is not wrong.

It is really hard to get an accurate estimate of the death toll, since you need a lot of contemporary records from many different places for this, but the source I read - a book called A Complete History of the Black Death by Ole (OO-la) Benedictow - took into account 300 demographic studies from all over Europe in order to come to this number.

In that book, the author throws some shade on other estimates as being based on bad math or on nothing at all, so if you see sources out there that say 30% died, 50% of people died, that is probably a drastic underestimate of the true scale of this disease’s death toll.

I’ve even seen those estimates in academic sources, uncited, as if it’s common knowledge.

Well, Mr. Benedictow painstakingly researched for decades the true death toll of the Black Death and put it all in the second edition of his book in 2021, so I’m going to go with his educated guess.

I can’t say numbers for sure for the rest of the areas affected by the Black Death, but the total number of dead in Europe is probably around 55-65 million dead.

In the space of 7 years.

I’ll talk more about places that were affected later, but it was primarily Europe.

To live through that - I can’t even imagine.

If you think living through the last few years of the COVID-19 pandemic were bad, as of recording this, just under 7 million people have died from Covid-19, but in a world population of 8 billion, that’s less than 0.01%, so it’s not even close to the scale that was seen back then.

Prior to the Black Death, about 443 million humans were alive.

After, by around the year 1400, there were only about 374 million people.

This disease would sweep in and wipe out more than half of your neighbours and family, within a few weeks or a month.

The devastation is unimaginable to anyone who hasn’t lived through a similar event.

Now, the first thing I’m going to ruin for you is that when we’re talking about the Plague, a disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the term ‘Black Death’ refers to a time period wherein the disease entered Europe, not the disease itself.

That time period is the years 1346 to 1353.

The plague has been killing people for thousands of years and has had several worldwide pandemics, but The Black Death refers only to 1346-1353.

So the year given at the beginning of the movie, 1348, is accurate, but I have opinions about that which I will share later.

Secondly, the word ‘germ’ mentioned in the opening, didn’t exist in 1348.

It wasn’t first used until 200 years later, and then it referred to a seed or material that germinates and grows into a larger organism.

It wasn’t used to mean an invisible microbe as we sometimes use it today.

Plague is fine, it’s a word first used in the mid-1300s, so we’ll give them that one.

According to records and writings of the time, people living through the Black Death called it the pestilence, the Great Mortality, the bumps disease, or simply the epidemic.

The term Black Death wasn’t coined until many centuries later.

It came from a Latin expression atra mors, where mors means death and atra can mean terrible or black metaphorically, as in dark or ominous.

Black is frequently mistaken for referring to the colour of the sores or gangrene that the plague causes, but this is just coincidence.

[CLIP, Ulrich: Word has reached the bishop of a village that does not suffer as the rest, time 10:32]

So the movie opens with Eddie Redmayne playing Osmund, a young man who intends to take vows as a monk, and he’s in isolation. There’s another monk who has died and is being taken away and inspected, showing burst sores on his armpits.

We see Osmund checking his own armpits, as a rat crawls ominously through the cell near him, but then Osmund asks if he can come out of quarantine because he says he has no signs of the disease.

He is released, and he immediately goes into the village to visit his secret girlfriend, and along the way you can see the scores of people who are dead and dying in the street.

At first glance it appears that there are a few historically accurate things here.

The monks and people carting bodies away are covering their faces with cloths and masks, but this is because back then the prevailing theory of disease spread was miasma.

They thought that disease was spread through bad smells, if you smelled something gross or if you smelled a dead body, then you could catch a disease, or whatever it was that killed the person.

This is where the name for malaria literally came from, mal aria, meaning bad air.

It was named because people way back when knew that if you went into the swamps, you were highly likely to catch malaria, but they thought it was because of the bad air, or the bad smells of a nasty rotting swamp, not that it was due to insect bites of the mosquitoes that lived there.

This is why in those classic plague doctor masks, the long noses were filled with things that smelled good, probably fruits, fragrant herbs or flowers, things that would block the bad smell because they thought it was literally blocking the disease, not just making it easier to breathe.

Plague doctors also wore a long waxed gown and had a stick to keep sick people away, and for a lot of things these strategies might have worked, but I think it was probably met with mixed success for the plague, and I’ll talk about that later.

After Osmund sees his girlfriend, he sends her away back to Dunwich Forest where the two of them came from, he says she’ll be safer there, and that he will meet her.

Then Sean Bean shows up as the character Ulrich, a knight sent by the bishop to find out the source of the plague and to find out if the rumours of a village spared the pestilence are true.

He is asking for help, a guide, and turns out that this village is supposedly right next to Dunwich Forest, so Osmund volunteers to guide them so he can meet his girlfriend.

They set out and meet up with a merry band of adventurers who have a huge cart full of lovely looking torture devices, as apparently their real mission is to find and kill a supposed sorcerer who’s been keeping this village free of plague.

They set off traveling slowly by horse and foot, and as they travel, they come across a woman being tied to a stake in preparation for being burned as a witch because the townspeople think she poisoned their well.

This was mentioned in the opening monologue also, that people were afraid and some had decided that the plague was god’s punishment, but others were convinced it was witchcraft, or the devil’s work.

Talking about this will stray a little far into the social history of the Black Death, rather than the science of it, and I don’t like to step outside my lane too much, but from what I’ve read, accusing people of being witches was in vogue for a while.

Over time, some turned away from calling it witchcraft, they turned to plague doctors and what I guess you could call the actual science of the day, such as it was, tonics and tinctures of herbs, that sort of thing.

In the face of this completely unknowable disease they turned to many things for help and explanation, as wave after wave of the pestilence hit them.

Speaking of the science, let’s get to that.

[CLIP, Voiceover, The plague, more cruel and more pitiless than war, descended upon us, time 1:00]

Just what exactly IS the plague?

There have been many different diseases that people call plague, but not all of them are THE plague.

This reminds me of that line from Once Upon a Time in Mexico where Danny Trejo says about El Mariachi, ‘They call him El - as in The’.

Well, this is THE plague.

There are a bunch of short-lived plagues or diseases in history that we have absolutely no idea what caused them, but we know weren’t caused by the plague bacterium, they were just called plague.

Contemporary records or descriptions of the disease either weren’t detailed enough for us to match the signs to diseases we know of today, or the symptoms described just don’t match any diseases that we know of.

There’s the Dancing Plague of 1518, the Sweating Sickness of 1485 to 1551, The Great Dying in New England in the year 1616…

There’s even the issue that so many things look exactly the same and might be described as so similar that we can’t tell the difference.

Just think how many different things there are that give you a fever, aches and pains, or an upset tummy. How many different cold viruses are there, how many different flu viruses are out there, where some are mild and some are deadly?

How do we know what caused the Black Death?

Well I’m glad you asked, let me tell you.

This is a bacterial disease caused by a little rod-shaped bacterium called Yersinia pestis.

It’s named for the scientist who researched and defined the disease in 1894, Alexandre Yersin, and pestis, the Latin word for pestilence.

Dr. Yersin was researching the plague in Hong Kong, presumably because the third historical plague pandemic began in the 1770s in China and had reached Hong Kong in 1894.

There are good records of the identification from back then, and this is a bacterium that is still around and still causing infections and problems today, so we have been able to map out the disease course, how it infects people, and what symptoms it produces.

We know now what to look for.

But the farther back in time you go, the harder it is to be really sure what someone died of.

For plague victims, especially those who died during the Black Death, we’re lucky in that there are good records, even from almost 700 years ago, of plague cemeteries where only those who died of the plague were buried.

The cemetery containing the bodies of plague victims that were used in proving Yersinia pestis as the culprit was the East Smithfield Black Death cemetery in London, and this work was done as part of a PhD thesis by anthropologist Dr. Sharon DeWitte at Pennsylvania State University.

Since this is a bacterial disease that travels in the blood, what Dr. Dewitte did was extract the dental pulp and test it to see if there was any Yersinia pestis present.

If you’re like me, the first thing you think of when you hear dental pulp is like, the gunk from between your teeth.

I don’t fault you for thinking that, but dental pulp is actually the part under the enamel where all the nerves and blood vessels are, so the good thing about that is that it’s very protected from decay, even across nearly 7 centuries.

You might not think it’s a big deal, or that it’s been settled for ages what caused the Black Death, but this was only solved for certain in 2010 to 2011 when papers were finally published with the results of this dental pulp testing.

Other theories were that it was anthrax, or an ebola-like virus, or even smallpox.

The plague and smallpox have even been mixed up or hard to distinguish in records because smallpox causes bumps that ooze and used to kill a lot of people also.

However, this is settled now because we have genetic testing.

We do have good contemporary descriptions of the plague during the Black Death, there’s a lot of art and writings about it from the time because so many people were affected.

And since the signs and symptoms match what we know happens to people still today who’ve died of or been infected with Yersinia, the scientists knew that this was likely the culprit.

There are a couple different ways to catch the plague, and it presents differently in your body depending on how you catch it.

The three main forms of plague are bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic.

Bubonic is the one you’re thinking of, where you get swollen lymph nodes called buboes in your groin, your armpit and on your neck. This is by far the most common and is the type that swept Europe during the Black Death and causes most infections today.

Bubonic plague is caught from a flea bite, or very rarely if you have a cut or open wound and come into contact with a person or animal that died of plague, if enough bacteria get into the wound, then you catch it that way.

Side note, this is why I don’t know if plague doctor coats would be that protective, because a flea can just jump onto your legs and nestle in your clothes that way, but it might have been a little successful in stopping fleas.

Non-flea transmission is not restricted to just fresh corpses, either, or the fleas jumping off of them and onto you.

There’s one report of a wildlife biologist who became infected with plague after finding a weeks-old dead mountain lion, and Dr. Yersin himself said that plague bacteria can live in soil and that people can catch it that way if you come into contact with it.

However you’re infected, it takes 3-5 days to develop symptoms. Some sources say 2-10 days, so it probably depends on the person.

In the Black Death time, people were described as developing boils at the site of flea bites, but this doesn’t happen in modern plague that we’ve observed.

Other general signs of infection are chills, sudden onset of fever, sore muscles and joints, pains in your limbs and abdomen.

And then your lymph nodes commonly in your armpits or your groin, depending on if you were bitten on your arm or your leg, and often on the neck also, they become swollen and can reach the size of an egg, about 10 cm across.

These buboes are very tender, like excruciatingly sore, they will turn black due to blood coagulation, they will tear open and ooze pus and fluid.

And then after about 3-5 days of this, about 60% of people will die if untreated.

Septicemic plague is the least common, likely caught in the same ways as bubonic, but it’s where the bacteria are reproducing to high numbers in your blood, rather than in your lymph nodes.

In septicemic, the bacteria cause an immune reaction that coagulates your blood in your extremities, which means fresh blood can’t get to places like your fingers, toes, your nose, your ears, so you get gangrene and die within a week.

Pneumonic plague occurs in one of two ways.

Your blood will carry the bacteria to your lungs, either from the flea bite directly, or maybe as secondary to bubonic or septicemic just from having such high numbers of bacteria in your blood.

The bacteria arrive at your lungs where they gather and cause clotting and massive tissue death, coughing, flu-like symptoms, shortness of breath, again a sudden onset of fever, then coughing up a lot of blood and then you die, usually in 2-4 days.

Septicemic and pneumonic are almost certainly deadly, but if you get treated within 18-24 hours of infection, it can take the mortality of pneumonic down to only 25-50%.

Pneumonic plague is the only kind that is transmissible from human to human, which happens when there’s so much bacteria in your lungs and you’re hemorrhaging and coughing, that you spray some bacteria out into the air and another person breathes it in.

Anyways, as I just mentioned, bubonic plague is caused by a flea bite.

Most often the rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, that lives on the common black rat, but currently we know that over 80 species of flea and 280 different mammals can carry the plague itself, from hamsters, gerbils, prairie dogs, and voles to cats, camels, foxes, coyotes, goats, and even one species of bird has been noted to carry plague.

Bubonic plague during the black death, though, was caused by rats and rat fleas.

And we can say we know this due to the unique way that the disease spreads.

Before I talk about spread during the Black Death period, I’ll just briefly mention the other two major plague pandemics.

The first major plague pandemic was the Justinian Plague, which began in the year 541 in Egypt, and then spread to Constantinople and the rest of the Mediterranean basin within a few years and then kept hitting the area every few years in 18-20 outbreaks of disease until about 750 CE.

It is named after the Roman Emperor of the Orient, aka the Byzantine Empire, at the time it hit, which was Justinian I, which is a bit unfair.

It’s not like the poor guy was living in a time when there existed a cure or even the science to understand and prevent the plague, but did nothing and refused to even try and keep his citizens safe.

No, he was just the major world ruler when it began, and by the time it ended, 10s of millions were dead, which is perhaps a third of the Mediterranean’s population at the time.

Skipping over the Black Death period for a moment, the third plague pandemic began in 1772 and ran until basically the end of world war 2, which is, coincidentally, when antibiotics became widely available.

The third pandemic began in southwestern China, and by 1900 the plague had invaded all continents except, I assume, the Antarctic.

It hit India in 1896, Japan in 1899, Saudi Arabia and Turkey in 1897, and basically everywhere else by 1900, including the Americas.

Canada, notably, has never had a detectable case of plague, so that’s yet another reason why I love living here.

We also have free healthcare that would take care of you if you did catch it.

Before antibiotics, two-thirds of people who caught the plague would die, and after antibiotics became accessible, that dropped to about 5-10%.

Except pneumonic, as I mentioned.

Since the year 2000, over 26,000 cases have been detected worldwide, including in the Americas (except Canada), and Asia, but with 97% of plague cases being in Africa.

During this third pandemic, and by studying current outbreaks of plague in Africa, it’s been found that outbreaks are very much linked to climate.

In several African countries, they’ve found that plague outbreaks are much less likely when the temperature is below 15 or above 27 °C.

Sorry Americans, I don’t know what that is in Freedom Units, but what it means is that basically this is very good evidence that this was primarily spread by insects.

Insects, and particularly the rat flea, don’t tend to survive cold winters and don’t spread disease as much.

It’s also related to rainfall and humidity.

In Vietnam, outbreaks were more common during the hot and dry times, when those periods followed recent heavy rainfalls.

This is because fleas require warmth and humidity to breed, but too moist or too warm and not only can the flea larvae and pupae physically not go through metamorphosis properly, the soil will grow fungi and molds that will destroy the flea eggs.

Rainfall also affects rodent burrows, because if there’s too much rain, the rodent burrows get flooded and that reduces their numbers.

Floods and cold weather also reduce the availability of food for rodents.

I am simplifying here, for my own sake as much as yours, but all of these factors are important in learning how diseases spread.

So, when a rat carrying plague-infected fleas gets into a new, uninfected colony, it will take about 2 weeks to kill all the rats.

Then, it takes about 3 days for the fleas who feed on blood to begin starving.

At this point, they’re going to turn to the closest animal.

And because the black rat, which is the main carrier, likes to live near humans, whereas the grey or brown rats don’t, humans are an easy next target for the fleas.

After that, it takes 3-5 days to develop an infection, and 3-5 more days to die of bubonic plague.

So when plague moves into a new area, the first human death will occur about 3-4 weeks later.

In smaller communities, it will be easier to notice a problem.

Historians have found that in towns of a few thousand, it took about 40 days for there to be some realization of the scale of what was going on during the black death.

In cities of 10,000 to 100,000, it could be 7 or 8 weeks before there were enough plague deaths, amongst all the other health issues in a city, that people started sounding the alarm.

Now, bring this all to the start of the Black Death period in 1346.

Somewhere on the northwestern shores of the Caspian Sea, the bacteria began to spread.

Maybe some rats got into a burrow with plague infested soil, or maybe some people stumbled on or through the rat warren and picked up some of the fleas.

The area at the time was ruled by the Mongol Horde

The Horde had been laying siege to the port of Caffa for a couple years, which is now called Feodosiya, in Ukraine.

Somehow, the Horde became besieged themselves, but by the plague, probably through reinforcements or supply deliveries, something like that.

To describe this, I want to read some of a nearly contemporary account because it is so descriptive and paints such a vivid picture.

This was written by Gabriele de Mussi (MOOSee), who was a notary in the Italian town of Piacenza.

It’s not thought that de Mussi actually witnessed what happened at Caffa, but this account was written probably in 1348 or 1349, so very shortly after, and is based on eyewitnesses so it’s presumed to be reliable.

I’ve abridged it a little, but the link to the full quote is in the sources.

It begins “In 1346, in the countries of the East, countless numbers of Tartars and Saracens were struck down by a mysterious illness which brought sudden death. Within these countries, broad regions, far-spreading provinces, magnificent kingdoms, cities, towns and settlements, ground down by illness and devoured by dreadful death, were soon stripped of their inhabitants.” [...]

“Oh God! See how the heathen Tartar races, pouring together from all sides, suddenly invested the city of Caffa and besieged the trapped Christians there for almost three years [...] behold, the whole army was affected by a disease which overran the Tartars and killed thousands upon thousands every day. It was as though arrows were raining down from heaven to strike and crush the Tartars’ arrogance. All medical advice and attention was useless; the Tartars died as soon as the signs of disease appeared on their bodies: swellings in the armpit or groin caused by coagulating humours, followed by a putrid fever.

“The dying Tartars, stunned and stupefied by the immensity of the disaster brought about by the disease, and realizing that they had no hope of escape, lost interest in the siege. But they ordered corpses to be placed in catapults and lobbed into the city in the hope that the intolerable stench would kill everyone inside. What seemed like mountains of dead were thrown into the city, and the Christians could not hide or flee or escape from them, although they dumped as many of the bodies as they could in the sea. And soon the rotting corpses tainted the air and poisoned the water supply, and the stench was so overwhelming that hardly one in several thousand was in a position to flee the remains of the Tartar army. Moreover, one infected man could carry the poison to others, and infect people and places with the disease by look alone. No one knew, or could discover, a means of defense.”

What this is describing is what is known as the first recorded incidence of biological warfare.

Cadavers would definitely have spread disease, though from their fleas and blood, not from the stench.

From this siege, people fleeing would have gotten onto ships and taken the disease from Caffa to Constantinople, and from there to Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Sicily and Sardinia, within 1346.

In the show notes there will be a link to my sources and transcript as always, and this time I will post a map of the spread by year, too.

By 1348, there are records of plague outbreaks just in the southern part of England.

All of this spread went slowly, month by month creeping across Europe by port cities, and then spreading inland.

The plague arrived in England on or around May 8th of 1348 via a ship from Bordeaux that landed at Melcombe Regis in Dorset.

The epidemic broke out June 24th, and spread inland slowly from there. It reached London in August and there were people writing about it in September.

At this time, about 90% of people in Europe were living in small towns and on farms in the countryside.

They lived often as tenant farmers and paid rents out of what they earned from their crops.

It was very low population density, but the unique thing about the plague is that it killed more people in the countryside than it did in the city.

We can look at death records and see this. It’s true across Europe, that the lower the population density, the higher the mortality.

This is different from pretty much every other disease out there, which kills more people when there’s more people around.

This is also how we can be sure that the main way plague spread was through bubonic and not pneumonic plague.

Pneumonic would spread faster and easier with more people being around, but not only that, it burns itself out too quickly because it kills so fast.

Fast killing diseases don’t tend to spread super far in general.

So how did this happen?

Mr. Ole Benedictow proposes that this is a unique feature of rats and rat fleas spreading disease, and the behaviour of the fleas.

I’ve already described how the rats will take about 2-3 weeks to all die, and then 3 days later the fleas are starving, and where are they going to turn? Humans.

For a rat colony of a given size with a certain number of fleas, when there are more people around, that’s fewer fleas per person, and so fewer bites, and a lower bacterial load.

On farms where perhaps only 1 family lives, maybe 4-5 people? That’s a lot more fleas per person, lots of bites, and they’re guaranteed to get a high dose of infectious bacteria, which kills them.

This is how we know it’s spread by rats and rat fleas, and how it killed so many people.

That, to me, that’s really fascinating.

It makes so much sense, and, of course, Benedictow backs this up with data for Europe.

The plague did also spread to North Africa and around the edges of the Mediterranean a bit, and while the Black Death period lasted only until 1353, the second pandemic was ongoing, hitting in 1363, 1374, 1383, all the way to 1670 almost without skipping a year, there were continuing outbreaks.

However, a few places in Europe did escape.

Iceland was spared the Black Death, but was hit in the early 1400s. Greenland and Finland also were spared the Black Death.

Notice it’s the colder, more northern countries?

In the plague history of Norway from the Black Death in 1348 through the end of 1654, there was never an outbreak of plague in the winter.

It cannot survive in the cold, which again reinforces that it’s an insect vector borne disease.

This brings me back to the beginning.

The movie says it’s 1348, and Osmund says at one point he’s from the Monastery at Staveley.

Staveley is in the north of England folks, way up past Blackpool, it’s practically Scotland.

From the plague maps that I’ve seen, this area wasn’t infected with plague in 1348, certainly not in the summer of 1348 as the plague was barely in England then, so I think a better year for this movie would have been 1349.

[CLIP, Ulrich, we travel into hell, but God travels with us, time 13:36]

Now, I’ve mentioned that the plague killed around 60-65% of people, but not everyone who became infected with plague would die.

There is a genetic condition called Familial Mediterranean Fever, or FMF, that does appear to confer some resistance to the plague, and I presume some other types of infections.

What FMF involves is mutations in the gene for pyrin, an immune protein that regulates fever, which is where the word ‘pyrin’ comes from, it’s the Greek word for fever.

Pyrin turns on your immune system and is critical in how your body can mount an immune response.

Mutations in the genes that control pyrin or in the pyrin gene itself, result in it being always on, or always being produced in your body to some level, not just when you’re sick.

In a normal body at rest, you don’t want your immune system to be always on like that, so having FMF means you have an always active immune response, and this results in abdominal pains, joint pain, arthritis, and cycling fevers that can last anywhere from 12 hours to 3 days.

Not a very nice thing to have.

However, when plague bacteria infect a person, they secrete molecules that downregulate your immune system, and in an average person, this means they just can’t mount an effective immune response and they die very quickly.

In a person with an immune activator gene that’s always on, it means they can fight off the bacteria much easier because their immune system is not suppressed and they will die from plague at a lower rate.

How this played out in the Black Death was not very much fun.

Obviously no one knew why certain groups of people with this mutation weren’t dying at the same rates as everyone else, so they were persecuted quite heavily.

What groups of people was it, you ask?

Familial Mediterranean Fever is seen mostly in people of Arab, Armenian, Jewish, or Turkish ancestry.

I can’t really take the time to get into this too much, because again this is more social and history which are not my areas of study.

I will link to a paper on this, which is unfortunately not open source, but if you have credentials you can read it, or there are books and websites you can look up and read if you want to learn more about this.

To sum up, there was a lot of persecution against people from these cultural groups, as well as Catalans from Spain, mendicants or beggars, foreigners of any kind, and women.

All of these groups were blamed, tortured, and killed for being the source of the plague.

There is another gene that’s had some mention of being helpful in resisting plague, and that is the gene for the cell surface receptor CCR5.

You might recognize this as being the gene can contain a deletion of part of its protein structure, called the ‘delta 32’ deletion, that leads to resistance to HIV.

From the bit of research I did, this resistance to plague is ambiguous at best, and probably doesn’t really have an effect in live animals just in cell culture in a dish.

Mice that were bred without the CCR5 receptor didn’t show a difference from wild type mice in how infected their cells became with Yersinia pestis.

Alright, now let’s talk about treatments for the plague.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the treatment was antiserum, which is antibodies purified from the blood of a person who has survived the plague.

This would reduce mortality to between 10-30%, but it’s only a short term thing and can have severe allergic reaction side effects if other blood proteins aren’t purified well enough, and you get them from someone with an incompatible blood type from yourself.

The good news is that there is very little recorded antibiotic resistance in plague, so currently you can use any antibiotic that you would use to treat something simple like E. coli.

Today, main treatments are streptomycin or gentamicin, or a combination of doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol.

Doctors tend to treat this very aggressively with multiple antibiotics because it is so deadly.

In the movie there’s an incident where a healer makes a poultice for someone who’s been stabbed, and this isn’t related to the plague, but as I was watching it made me go down a huge rabbit hole trying to figure out what this might have been.

It looked to me like a moss of some kind, but when it was applied, it immediately stopped the pain.

I don’t think there are any mosses that produce pain killers, but there are several other plants that do.

Of course we know about willow bark, but this mixture didn’t look like bark to me, it was definitely leafy and green, which leads me to maybe something from the lamiaceae family.

Lamiaceae are commonly herbs and include things like rosemary, marrubium, which is a flowering shrub with some antimicrobial activity, ironwort also known as Greek mountain tea, and peppermint and other mints.

All of these, plus many more members of the same family, have been shown to have some mild analgesic effects.

One or more of these could’ve been in there, even though it looked like moss and not rosemary or peppermint.

I guess moss looks cooler and more swamp witchy.

Now, finally, lastly, I want to talk about a few depictions of bubonic plague in the movie.

There are a few characters who catch it on this journey to hunt for the supposed sorcerer.

I don’t think this movie has been seen by enough people that I can assume most people know the ending, and since I hate giving spoilers, I won’t say who it is, but a couple characters do display buboes on their bodies.

One suddenly starts coughing and then reveals he has a large buboe on his neck.

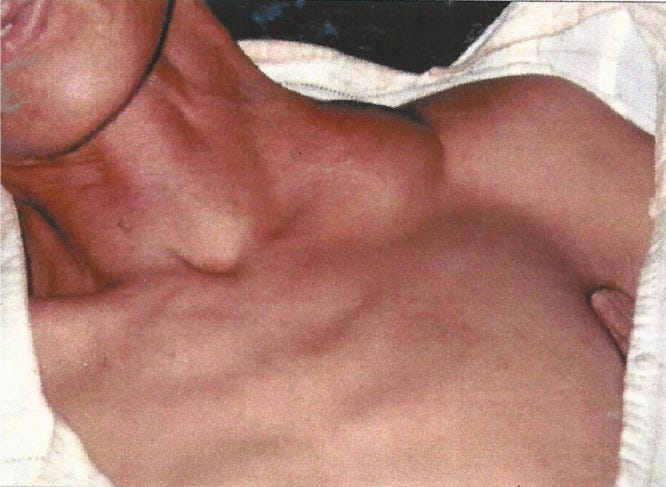

And then at the end another character reveals that he has multiple buboes in both armpits that have burst and are oozing pus and blood everywhere.

These buboes were a surprise in both cases as no one was showing any symptoms at all, and from what I know, this isn’t correct.

As I described the symptoms, patients would be very sore, have abdominal pains, sudden onset of high fevers, and the buboes would be excruciatingly painful.

It would just be ‘surprise, I’m sick’, they would likely drop and be unable to move on initially, and then develop buboes over the next day or so.

It does make for a sweet ending, though.

Except for that part where I said that bubonic plague is not spreadable from human to human, but I guess the guys would’ve been carrying fleas, too.

Now if you’re wondering whether or not Sean Bean lives, well, like I said, I don’t like spoilers, you’ll just have to go watch it yourself!

I think it’s worth it, but this movie is not for kids, so please don’t traumatize your children with it.

MUSIC OUTRO

Alright folks that’s all I have for this episode of Tierah Ruins Things with Science. I am a researcher, not a doctor, so please don’t take any of this as medical advice, as it is for entertainment only.

You can follow me on twitter at biologycellfies, facebook at Tierah Ruins Things With Science, and tiktok at tierahruinsthings. I’ll put those names in the show notes, as well as a link where you can see all my sources and a transcript.

I did all the research, writing, and recording.

Music was written and provided by James Stratton-Crawley, and there’s a link to his channels in the show notes. He also helped me with the editing.

If you have any suggestions for tv shows or movies featuring diseases or pathogens that you’d like me to cover, send them in to tierahruinsthings@gmail.com

See you all next time where I will be talking about The Tomorrow War which has some questionable understanding of how toxins and anti-toxins work.